About Ethiopian Jewry

The Beginning of Jewish Settlement in Ethiopia

Until the 14th century, the history of the Jewish community in Ethiopia (Beta Israel) was rarely recorded in written sources. Instead, it was preserved primarily through oral traditions passed down from generation to generation. As a result, the origins of the community and the time at which it arrived in Ethiopia are unknown. Over the years, several hypotheses have been proposed:

- The community traces its origins to the Tribe of Dan, which is said to have gone into exile from the Land of Israel as part of the exile of the Ten Lost Tribes, or possibly even earlier, during the period of the division of the Kingdom of Israel. The existence of an exiled Jewish community in Cush is mentioned in the writings of the prophets: “On that day the Lord will extend his hand yet a second time to recover the remnant that remains of his people, from Assyria, from Egypt, from Pathros, from Cush … He will raise a signal for the nations and will assemble the outcasts of Israel, and gather the dispersed of Judah from the four corners of the earth” (Isaiah 11:11–12).

It should be noted that the Book of Isaiah does not associate this community specifically with the Tribe of Dan. That connection appears for the first time in the writings of Eldad the Danite from the ninth century CE, and later in various rabbinic sources, including the writings of Rabbi David ben Zimra (the Radbaz). This tradition, among others, formed the basis for the ruling of former Chief Rabbi Ovadia Yosef that Ethiopian Jews are indeed Jewish. - The community originated among Jews who migrated from Egypt at various points beginning in the seventh century BCE, following internal disputes within the Jewish community or persecution from external forces. This hypothesis is based on traditions preserved within the community and is also supported by some scholars of Ethiopian Jewry, who point to similarities between the practices of the ancient Jewish community of Yeb (Elephantine) in Egypt and those of the Beta Israel. According to a widely held version of the community’s tradition, the Jews migrated south along the Nile from Egypt to Sudan, entered Ethiopia through the regions of Qwara and Tigray, and from there spread to other areas.

- The ancestors of the community migrated from southern Arabia (Yemen), where a large Jewish community once existed. This hypothesis, which is also widespread among scholars, is based on the geographic proximity of the two regions and on abundant evidence of commercial, cultural, and political ties between them beginning in the early first millennium BCE.

- The earliest members of the community arrived in Ethiopia during the reign of King Solomon. This is the Ethiopian national tradition, which expands on the biblical account of the meeting between Solomon and the Queen of Sheba. According to the tradition, their encounter resulted in the birth of a son named Menelik, who was raised in Ethiopia. As an adult, Menelik traveled to Jerusalem to visit his father, and at the end of his stay, representatives of the tribes of Israel were sent with him to accompany him back to Ethiopia. From these companions, the community is said to have emerged. This tradition forms part of the Ethiopian national epic, the Kebra Nagast, and is also known within the Beta Israel community.

- According to this theory, the Beta Israel did not originate as an ancient Jewish community, but rather emerged from Christian Ethiopians of the Agaw people who adopted Judaism in the 14th and 15th centuries. This view has been proposed by some scholars in recent decades, partly because Ethiopian royal chronicles mention Jews in the kingdom only from the 14th century onward. The community itself firmly rejects this interpretation. In addition, most scholars recognize that the community existed in Ethiopia in much earlier periods, even before Christianity was introduced to the region.

Evidence from Antiquity and the Early Middle Ages

The Kingdom of Aksum, which flourished between the 1st and 7th centuries CE and encompassed much of present-day northeastern Ethiopia and Eritrea, was one of the most significant powers of the ancient world. Its official language, Ge’ez, includes words derived from Jewish Aramaic, reflecting a Jewish cultural influence on the kingdom.

In the 4th century, as the rulers of Aksum converted to Christianity and declared it the official religion of the kingdom, the rulers of the neighboring Himyarite Kingdom in Yemen, across the Red Sea, embraced Judaism, which then became that kingdom’s official religion. In the 6th century, following a prolonged conflict between Aksum and Himyar that was also perceived as a religious struggle between Christianity and Judaism, the Kingdom of Aksum conquered Himyar and installed a Christian ruler in this kingdom.

The Kingdom of Aksum gradually declined during the 7th and 8th centuries. According to Ethiopian tradition, shared by both Jews and Christians, the kingdom was conquered and the city of Aksum destroyed by a Jewish queen named Judith (Yodit), who was said to belong to the Gideonite dynasty. Sources from the 10th century do mention a queen who conquered large parts of Ethiopia, although they do not provide further details about her identity.

Eldad the Danite, a 9th-century traveler who visited various Jewish communities across the Middle East, wrote that he came from the Tribe of Dan, which resides in the land of Cush alongside other tribes of the Ten Lost Tribes, and that these tribes were “fighting to this very day with the kingdoms of Cush.” In the 12th century, the traveler Benjamin of Tudela described independent Jewish communities living in high mountain regions in the Land of Aden, who would descend into the land of Lubiya (possibly Nubia, i.e. present-day Sudan) and fight against its Christian inhabitants. Some scholars have suggested that these accounts may refer to the Jews of Ethiopia.

The Gideonite Kingdom

The prevailing narrative of Jewish history in the Diaspora suggests that from the Roman defeat of Jewish rule in Judea until the establishment of the State of Israel, Jews lived for nearly 2,000 years as minorities under foreign rule. However, there were a few cases of Jewish autonomy in the Diaspora during antiquity and the early Middle Ages. Yet the only Jewish community to preserve its independence into the modern era was the Beta Israel.

Reports of the community’s heroic battles against the Christian Solomonic kingdom circulated widely throughout the Jewish world and became a source of inspiration across the Diaspora. For Jews in Europe and the Middle East, who lived under Christian or Muslim rule and often faced persecution and restrictions, the knowledge that Jews in Ethiopia had their own kings and army, and were courageously fighting against a Christian kingdom, was profoundly moving. Many Jews across Europe and the Middle East looked to the existence of a Jewish kingdom in Ethiopia as a symbol of hope and source of inspiration.

Toward the end of the 13th century, the Christian Solomonic dynasty rose to power in the northeastern Ethiopian highlands. In the years that followed, it expanded its rule into regions inhabited by the Beta Israel community. At the Solomonic court, chroniclers were tasked with recording the reigns of successive kings, and through their writings we have detailed accounts of the dynasty’s military campaigns against the Beta Israel community. Additional descriptions of these campaigns, and of the community’s rule over parts of Ethiopia, appear in the writings of Muslims from the Middle East and Christians from Europe who visited Ethiopia at the time. They also appear in the writings of Jews in Egypt and the Land of Israel, who encountered Ethiopian Jews who had arrived as pilgrims or as prisoners of war sold into slavery and who recounted events unfolding in Ethiopia.

Traditions about the Jewish kingdom in Ethiopia and the community’s heroic battles against the Solomonic dynasty were also preserved orally within the community itself. In these traditions, the kingdom is known as the Gideonite Kingdom, named after the ruling dynasty whose kings were called Gideon (Gedewon). Indeed, contemporary written sources from the period of the community’s rule also mention leaders named Gedewon, alongside leaders bearing other names.

One of the most devastating episodes in the history of the Beta Israel community was the military campaign led by the Solomonic emperor Yeshaq, who ruled from 1414 to 1429/30. Prior to this campaign, the community controlled an extensive territory that included Tselemt/Tselemti, Simien, Wegera (Wogera), and Dembya. Yeshaq marched with his army into Wegera and defeated the forces of the Beta Israel community there. He confiscated the fertile lands of Dembya and Wegera, redistributed them to his supporters, and established churches in the conquered areas to entrench Christianity and memorialize his rule. He also proclaimed: “Whoever is baptized in the Christian baptism shall inherit the land of his forefathers; otherwise, he shall be dispossessed of his ancestral land and become a Felase (landless person, arguably the origin of the term Falasha).” In other words, members of the community who refused to convert to Christianity would lose their land. After the war, Jewish rule remained only in the Simien Mountains and in the district of Tselemt/Tselemti.

Following the community’s defeat in the war and the decrees imposed by the emperor against those who remained faithful to Judaism, the very continuity of the Beta Israel community was placed in grave danger. According to the community's tradition, this crisis was overcome through the leadership of Abba Sabra, regarded as one of the greatest spiritual leaders in the community’s history, and his disciple Saga Amlak. They traveled among the various settlements in which the community lived, served as spiritual teachers, and worked to ensure the survival of Jewish religious life.

Abba Sabra is traditionally credited with religious writings, prayers, and legal rulings that shaped the community’s practices. These include aspects of the laws of ritual purity, which created clear physical and social boundaries between Ethiopian Jewry and the surrounding non-Jewish society. In doing so, they strengthened religious identity and helped prevent assimilation at a moment of profound vulnerability.

In 1529, Ahmad ibn Ibrahim al-Ghazi, a charismatic Muslim ruler who united the Muslim populations living south and southeast of the Solomonic kingdom, launched a campaign of conquest during which he succeeded in overrunning nearly the entire Solomonic realm. At the time, a Solomonic stronghold remained in the heart of the Simien Mountains and had managed to subjugate the surrounding Jewish population. The Jews of Simien initially assisted the Muslim army in capturing the stronghold; however, in 1542 they shifted their allegiance and supported the Solomonic emperor Gelawdewos.

Around the same time, a Portuguese military contingent armed with firearms arrived to assist the Solomonic forces in their war against the Muslims. The Jewish governor of Beyeda proposed that the Solomonic and Portuguese commanders jointly capture the Beyeda plateau from Muslim control, and this plan was successfully carried out. Later, when the Solomonic and Portuguese armies suffered a defeat at the hands of the Muslims, they retreated to Beyeda. There, in the heart of the Gideonite Kingdom’s territory, they regrouped and prepared for the decisive battle at Wayna Daga. In this battle, the Muslim leader was killed, and in its aftermath Solomonic rule was restored over northern Ethiopia.

The weakening of the Solomonic kingdom as a result of the war led to growing instability in its southern regions. Seeking a safer location for their capital, the Solomonic rulers chose the area northeast of Lake Tana, at the heart of the territory inhabited by the Beta Israel community and not far from the Gideonite Kingdom. It is likely that the desire to exercise complete control over all territories surrounding the Solomonic capital prompted the rulers to invest considerable effort in their military campaigns against the Beta Israel community during this period.

The Solomonic emperor Sarsa Dengel (r. 1563–1597) launched a series of campaigns against Radai, Kalef, and Goshen, the Jewish rulers of the Simien region, and succeeded in capturing their strongholds. During the battle for Kalef’s fortress, Jewish defenders rolled massive stones down from the heights onto the Solomonic soldiers. The Solomonic army, however, made use of cannons, a technological innovation in Ethiopia at the time, and was thus able to turn the tide of battle.

One act of exceptional heroism by a woman of the community during this battle became particularly well known. It is described in a chronicle written by Sarsa Dengel’s royal scribe, who was present on the campaign. Joseph Halévy translated the passage as follows:

A remarkable incident occurred at that time involving a captive woman, whom her captor was leading with her hand bound to his. When she saw that they were walking along the edge of a deep ravine, she cried out, “Lord, help me!” and threw herself into the ravine, pulling down with her the man who had bound her hand to his against her will. How extraordinary was the courage of this woman, who chose to risk her life rather than submit herself to the Christian man. Nor was she alone in doing so; many other women acted in the same way. But she was the first whose deeds I witnessed.1

In the aftermath of the fighting, Radai surrendered and was taken captive, and his crowns were seized as spoils by the Solomonic army. When Goshen’s stronghold was captured by Solomonic forces, Goshen threw himself from the top of a cliff and was killed. Gedewon managed to escape and continued to maintain his rule in the Simien region in the years that followed.

Sarsa Dengel married Harego, Gedewon’s sister, and they had a son, Ya‘eqob (Jacob), who for a brief period was crowned emperor of the Solomonic kingdom. When the Solomonic nobility conspired against him, Ya‘eqob attempted to flee to his uncle Gedewon in Simien, but he was captured and exiled, and Zadengel was crowned emperor in his place. After the nobility rebelled against Zadengel as well and he was killed in battle, Ya‘eqob returned to the throne.

At that point, another claimant emerged, Susenyos, the great-grandson of the Solomonic emperor Lebna Dengel. Ya‘aqob was killed in battle, and Susenyos ascended to the throne. Two other sons born to Harego, Gedewon’s sister, and Sarsa Dengel later attempted to restore control of the Solomonic kingdom with Gedewon’s assistance. Susenyos captured them and had them executed.

Gedewon did not forget the bloodshed that Susenyos had inflicted on his family and took advantage of moments of opportunity to support rebellions against his rule. Susenyos, for his part, launched a series of military campaigns against Gedewon. Following the first campaign, in which Gedewon surrendered, Susenyos attempted to forcibly convert the Jews of the Dembya region to Christianity. At the same time, he carried out massacres of Jews in Simien, Wegera, Belessa, and Janfankara. In the second campaign, the Jews emerged victorious, and Susenyos was forced to station guards around the Simien Mountains without managing to conquer them. After Gedewon was killed in battle against Solomonic forces, Susenyos launched another campaign in 1626, in which he finally defeated and brought an end to the Gideonite Kingdom.

1.J. Halévy, La guerre de Sarṣa Děngěl contre les Falachas. Texte Éthiopien. Extrait des Annales de Sarṣa Děngěl, roi d’Éthiopie (1563-1597). Manuscrit de la Bibliotheque Nationale nº 143. Fol. 159 rº, col. 2 – fol. 171 vº, col. I, Paris 21907, p. 86

From the Gondar Period to the 20th Century

Susenyos’s son, Fasiledes (r. 1632–1667), established his capital in Gondar and built his palace there. From his reign until that of Emperor Tewodros II (r. 1855–1868), Gondar served as the capital of the Solomonic kingdom. Around Fasiledes’ palace, a complex of royal residences was constructed, and throughout the city and its surroundings churches and compounds were built to serve the Solomonic nobility.

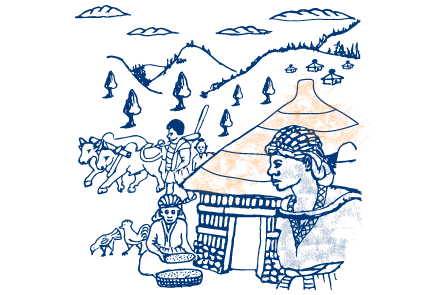

During this period, many members of the Beta Israel community became known as skilled builders and played an important role in the construction of the royal compound and public buildings in the city. In the years following the founding of Gondar, the community experienced a period of prosperity, and some of its members held senior positions in the administration and the army and were granted land in recognition of their service. Beginning in 1769, however, the central authority of the Solomonic kingdom weakened significantly. This decline undermined security, reduced construction activity in Gondar, and limited opportunities for members of the community to continue working in this field.

Between 1888 and 1892, Ethiopia was struck by one of the gravest disasters in its history, which also exacted a devastating toll on the Beta Israel community. This period, known as Kifu Qen (“the Evil Days”), saw a convergence of natural disasters and wars that led to widespread famine and epidemics. The prevailing estimate is that the years of Kifu Qen resulted in the deaths of between one-third and two-thirds of Ethiopia’s Jewish population.

Connections Between the Community and the Global Jewish World

As noted above, letters written by Jews in Egypt and Jerusalem as early as the 15th and 16th centuries mention Jews from Ethiopia who arrived in Egypt and the Land of Israel, some as pilgrims and others as prisoners of war. The arrival in Egypt of Ethiopian Jews who had been sold into slavery prompted a halakhic debate within the Egyptian Jewish community regarding their status, since Jews are obligated to redeem Jewish captives. The ruling of Rabbi David ben Zimra (the Radbaz), the leading rabbinic authority in Egypt at the time, which recognized the Jewish status of Ethiopian Jews, later served as a precedent for Rabbi Ovadia Yosef in his responsum affirming the Jewish identity of the community.

Contact between Ethiopian Jewry and the broader Jewish world is documented again from the mid-19th century onward. In the 1840s, correspondence took place, mediated by the French scholar Antoine d’Abbadie, between Abba Yeshaq, the senior religious leader of the community at the time, and his disciple Tsegga Amlak, and the Italian Jew Ohev-Ger Luzzatto. In 1855, a member of the community, Daniel ben Hanania, arrived in Jerusalem together with his son and spent several months among the local Jewish community.

In 1860, a Protestant mission was established in Ethiopia with the aim of converting the Jewish population. The missionaries and converts clashed with the community’s spiritual leadership and even succeeded, for a time, in prompting the authorities to impose restrictions on the community’s ability to offer sacrifices, a central element of its religious tradition.

Against the backdrop of this crisis, and amid deep hopes for redemption and longing for Jerusalem, a mass journey set out in 1862 under the leadership of the religious leader Abba Mahari, heading toward the Land of Israel. Many perished along the way, and those who survived eventually returned to their homes. Yet even though the journey did not reach its destination, it remains to this day a powerful symbol of the community’s yearning for Jerusalem, expressed not only in longing but also through extraordinary action.

Reports of missionary activity prompted the Jewish world to take action and strengthen its ties with Ethiopian Jewry. In 1867, the first emissary of the wider Jewish world, Joseph Halévy, arrived in Ethiopia. About thirty years later, his student Jacques Faitlovitch followed, devoting his life to fostering connections between the community and world Jewry. His work included advocacy efforts, fundraising, combating missionary influence, and establishing educational infrastructure. Selected young members of the Beta Israel community were sent to study in Europe, and some later went on to serve in the Ethiopian government and in community leadership roles. Among them were Tamrat Emmanuel, Getachew Yirmiahu, Yona Bogale, and Tadesse Yaakov.

In the early decades of the 20th century, ties between Ethiopian Jews and Jewish and Zionist leadership in Europe and the Middle East grew stronger. For example, in the 1950s, two groups of young people from Ethiopia arrived for several years of training at Kfar Batya, so that they could return to their communities and serve as teachers. However, these connections with state institutions did not develop into immigration to Israel until the 1970s.

Immigration to Israel

Longing for Zion has been an enduring part of the community’s life, expressed in songs, prayers, and the festival of Sigd, in visits by members of the community to Jerusalem at various times, and, as noted above, in the mass migration attempt of 1862. Shortly before the establishment of the State of Israel, and during the first decade of its existence, a small number of Beta Israel families immigrated to Israel, some of them together with Jews from Yemen. However, the state chose not to initiate organized immigration efforts, in part because there was no consensus in Israel regarding the Jewish status of the community, a position that also denied its members the right to immigrate under the Law of Return. In addition, government officials raised doubts about the ability of Ethiopian Jews to integrate socially and culturally into Israeli society.

Despite the state’s reservations, young people from the community occasionally arrived in Israel on their own initiative, ostensibly as tourists or for employment. Over time, some were required to undergo conversion as a matter of stringency, which granted them the status of new immigrants. Others remained in the country without legal status, and deportation orders were issued against them.

As a result of sustained pressure exerted by the community on the establishment, in 1973 the then Sephardic Chief Rabbi of Israel, Ovadia Yosef, ruled that Beta Israel are Jews. The state did not rush to implement this ruling and formally applied the Law of Return to Ethiopian Jews only in 1975. Even then, it continued its policy of refraining from initiating organized immigration, and until 1977 only about 200 Ethiopian-born Jews were living in Israel.

This small community worked tirelessly to promote the immigration of Beta Israel through petitions, demonstrations, and meetings with government officials in Israel and abroad. In addition, with the support of the American Association for Ethiopian Jews (AAEJ), several activists undertook advocacy efforts around the world to raise awareness of the issue among foreign governments and Jewish communities in the Diaspora, which in turn exerted pressure on Israel.

The struggle for immigration bore fruit with the rise to power of Menachem Begin, who made bringing the community to Israel a national objective. The first attempt took place in 1977, when a secret agreement was signed between the State of Israel and Ethiopia, which at the time had no diplomatic relations with Israel. Under the agreement, Israel was to provide military assistance to Ethiopia in exchange for permission for about 200 Ethiopian Jews to immigrate to Israel under the framework of family reunification. After 121 immigrants had arrived, the then foreign minister, Moshe Dayan, revealed the existence of the agreement to the media, and the immigration effort was halted.

In 1979, immigration from Ethiopia resumed after contacts were established between activists such as Ferede Aklum, Baruch Taganya, Zimena Berhanu, and Zecharia Yona, and the Mossad. With the assistance of these activists, the groundwork was laid for a new immigration route. Tens of thousands of community members then set out on a grueling journey on foot to Sudan, from where they were brought to Israel clandestinely.

The journey lasted weeks and sometimes months. Along the way, the travelers were forced to hide from government soldiers and bandits and to cope with harsh terrain, as well as severe shortages of food and water. Upon reaching Sudan, members of the community were often required to wait for months or even years in refugee camps before an opportunity arose to immigrate. Conditions in the camps were poor, both nutritionally and hygienically, and the refugees were subjected to harassment by Sudanese authorities and by non-Jewish refugees. Many of those who dreamed of reaching Jerusalem were overcome by these harsh conditions and lost their lives during the journey or while waiting in the camps. It is estimated that during these years about 16,000 people reached Israel, while approximately 4,000 perished along the way.

The Sudanese immigration route remained active for about a decade and was carried out in cooperation with the Mossad, community activists, the Israeli Air Force, and the Navy. It included operations of varying scope, the largest of which was Operation Moses (November 21, 1984–January 5, 1985). During this operation, more than 6,000 immigrants were brought to Israel. It was the result of a secret agreement reached with the Sudanese government through American mediation. After about six weeks, the operation was halted following leaks by Israeli sources to the media, which caused severe embarrassment to the Sudanese authorities.

Nevertheless, smaller-scale operations continued throughout the 1980s. During these years, immigration activists in Israel continued to pressure the state not to relent in its efforts to bring the remaining Jews of Ethiopia to Israel.

At the end of 1989, diplomatic relations between Israel and Ethiopia were renewed after a 16-year rupture, and the state began bringing members of the community directly from Ethiopia. Encouraged by community activists and Jewish organizations, foremost among them the AAEJ, many people left their villages and gathered around the Israeli embassy in Addis Ababa. At first, immigration proceeded at a slow pace, to the deep frustration of the community in Israel. Community leaders pressed the state to accelerate the process and to reunite families that had been separated after immigration from Sudan was halted. The pressure intensified as the security situation in Ethiopia deteriorated due to the ongoing civil war. Indeed, in April 1991, a decision was made to urgently evacuate all residents of the compound as rebel forces drew closer to Addis Ababa.

The Israeli government began preparations for a complex immigration operation in cooperation with the Israel Defense Forces, the Mossad, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, the Jewish Agency, and veteran immigrants from Ethiopia. The operation, known as Operation Solomon, was launched on the night of May 23, 1991, and became the largest immigration operation in the history of bringing Jews to Israel. Over the course of 36 hours, more than 14,000 immigrants were airlifted to Israel in a massive operation involving 34 aircraft.

Following Operation Solomon, the state sent emissaries to the Qwara region, access to which had been difficult during the 1980s due to rebel control of the area. Between 1992 and 1999, the residents of this region also immigrated to Israel.

The last community to immigrate, a process that in effect continues to this day, is the community known as the descendants of Beta Israel, also referred to as the Falash Mura or the remnant of Ethiopian Jewry. The roots of this community lie in members of Beta Israel who converted to Christianity from the 19th century onward but did not fully assimilate into the surrounding Christian society. Instead, they remained in a kind of intermediate position between the two communities and, at times, even maintained social ties with their Jewish relatives and with the Jewish community more broadly.

The question of this community’s immigration is complex. Most of its members are not eligible to immigrate under the Law of Return, yet many have close family ties to Ethiopian Israelis already living in Israel. In addition, many members of the community undergo preparatory conversion processes in Ethiopia while awaiting a decision on their status. Over the years, several waves of immigration of descendants of Beta Israel have been approved, bringing a total of about 50,000 people to Israel. Nevertheless, thousands remain in Ethiopia and continue to seek immigration.

As of the end of 2024, the community of Ethiopian Israelis numbered approximately 177,600 people, including about 93,400 who were born in Ethiopia and about 84,200 who were born in Israel.

The Spiritual Leadership of Beta Israel

The spiritual leaders of the community, the kahenat (qesoch, priests) and the maloksewoch (monastics), were the flame that sustained the faith and guided the path of Ethiopian Jewry. Knowledge of the Torah, the commandments, and religious law was entrusted to them. They led religious ceremonies and, when necessary, exercised moral and spiritual authority within the community. Their deep learning and ethical standing granted them leadership not only within the community itself but also in its relations with the surrounding society. They were also responsible for resolving disputes in cases where the shmagloch, the community elders, were unable to reach an agreement.

The path to becoming a qes began at a young age, usually around seven or eight. The candidate lived in a boarding setting under the supervision of the maloksewoch and studied continuously until he underwent a formal examination and received ordination. Ordination was granted only after marriage, and the community itself had to affirm him as worthy of serving as its spiritual leader. At the apex of the religious hierarchy stood the liqa kahenat, the chief priest, elected by all the religious leaders of the district and serving as the highest spiritual authority in the region.

A qes could marry only a virgin woman and was not permitted to divorce except in extreme circumstances, and even then only after a review by senior qesoch, who alone could authorize the divorce without harming his standing. A widowed qes was likewise permitted to remarry only a virgin woman, regardless of whether he was young or advanced in age. After receiving ordination from the monastic leaders, a formal ordination ceremony was held with the participation of the senior qesoch of the village. Conducted in the presence of the wider community, the ceremony was accompanied by a large communal feast, blessings, and songs of praise.

The title of qes carried profound significance among Ethiopian Jews. The qesoch guided village life and ruled on matters of communal importance. Their role embodied ideals of purity, integrity, dignity, and gentle conduct; they were moral exemplars whose lives were devoted to serving the community.

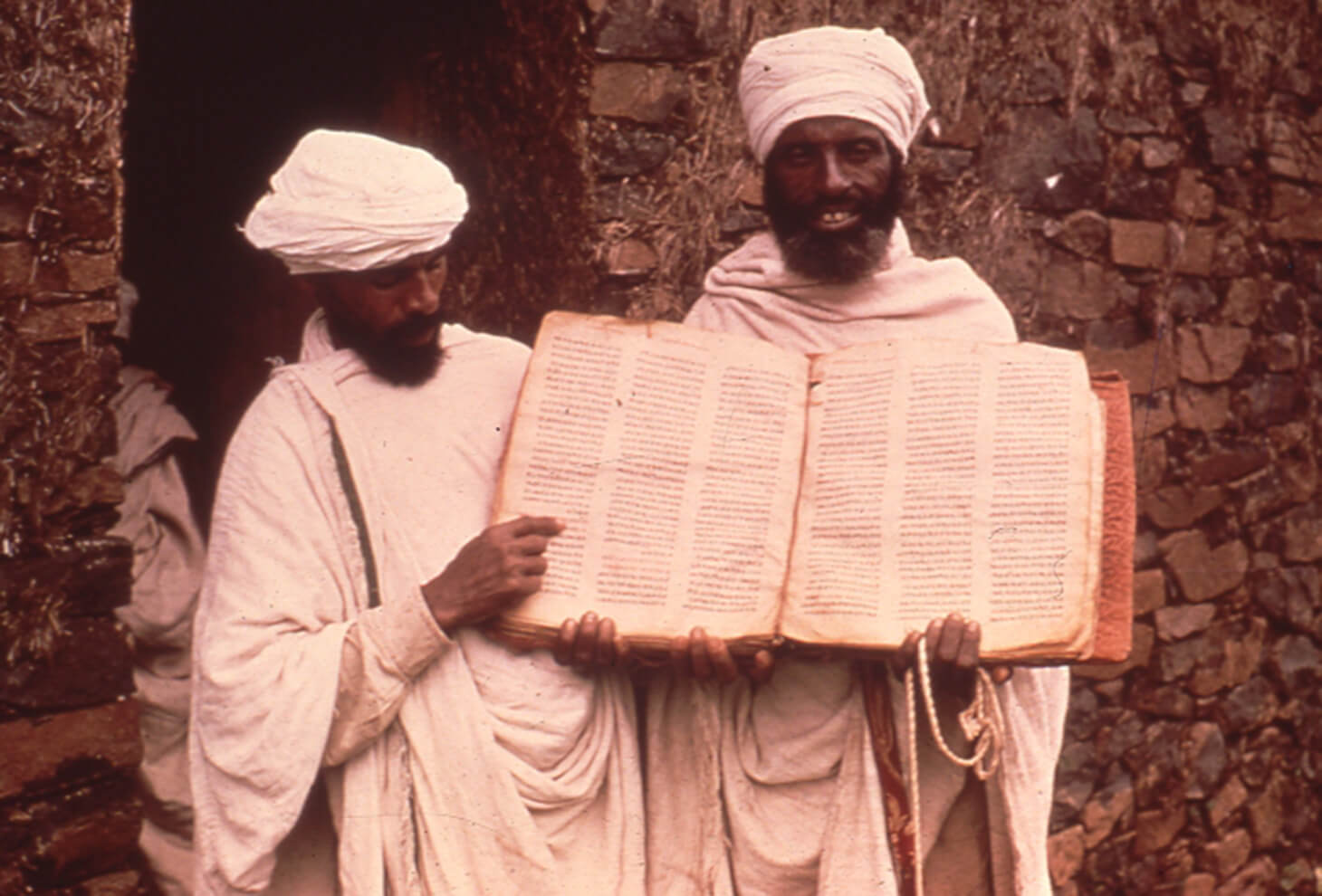

The qesoch always wore white garments, symbolizing purity and spiritual cleanliness. They wrapped their heads in white turbans and carried sacred texts with them. The qes fulfilled three central roles. The first was religious and included leading prayers on weekdays and holy days, offering sacrifices on festivals, issuing rulings on matters of ritual purity as well as marriage and divorce, and teaching Torah. The second role was social: the qes safeguarded the cohesion of the community, mediated disputes and conflicts, and had the authority to impose sanctions on those who defied communal norms. The third role was the acceptance of converts into the community.

Because the qesoch generally did not engage in agriculture like most other members of the community, but devoted their time to religious study and leadership, they lived modestly and were supported by first fruits and donations given by community members. Every large village had qesoch, who also provided religious and communal leadership to the smaller neighboring villages.

Another spiritual leadership role within the Beta Israel community was that of the malokse, the monastic. The maloksewoch were individuals who withdrew from communal life and lived in seclusion in order to devote themselves entirely to the study of the Torah. They were regarded as custodians of the deepest secrets of the faith and, as noted, served as the teachers and ordainers of the qesoch. The maloksewoch stood at the very apex of the community’s spiritual leadership and shaped many central aspects of Ethiopian Jewish prayer and religious law. According to tradition, some among them even attained the level of prophecy.

From the late 19th century onward, the number of maloksewoch gradually declined. In places where no maloksewoch remained, the qesoch assumed their responsibilities, training and ordaining the next generation of priests and leading the religious life of the community.

The maloksewoch observed especially stringent standards of ritual purity and refrained from physical contact with other members of the community. Their students, during the period of their training for the priesthood, were required to follow the same practices. According to community tradition, appointment to the role of malokse, like the appointment of a prophet, was determined by God. A student who received a divine calling to become a malokse remained in a state of ritual purity after completing his studies and was ordained as a malokse. A student who was not chosen for this role returned to the community at the end of his studies and was ordained as a qes.