Absorption of Ethiopian Immigrants

Immigration from Ethiopia via Sudan in the eighties and direct immigration in the nineties brought Ethiopian Jews (Beta Israel) to Israel, in two primary operations: Operation Brothers throughout the eighties, and Operation Solomon in 1991.

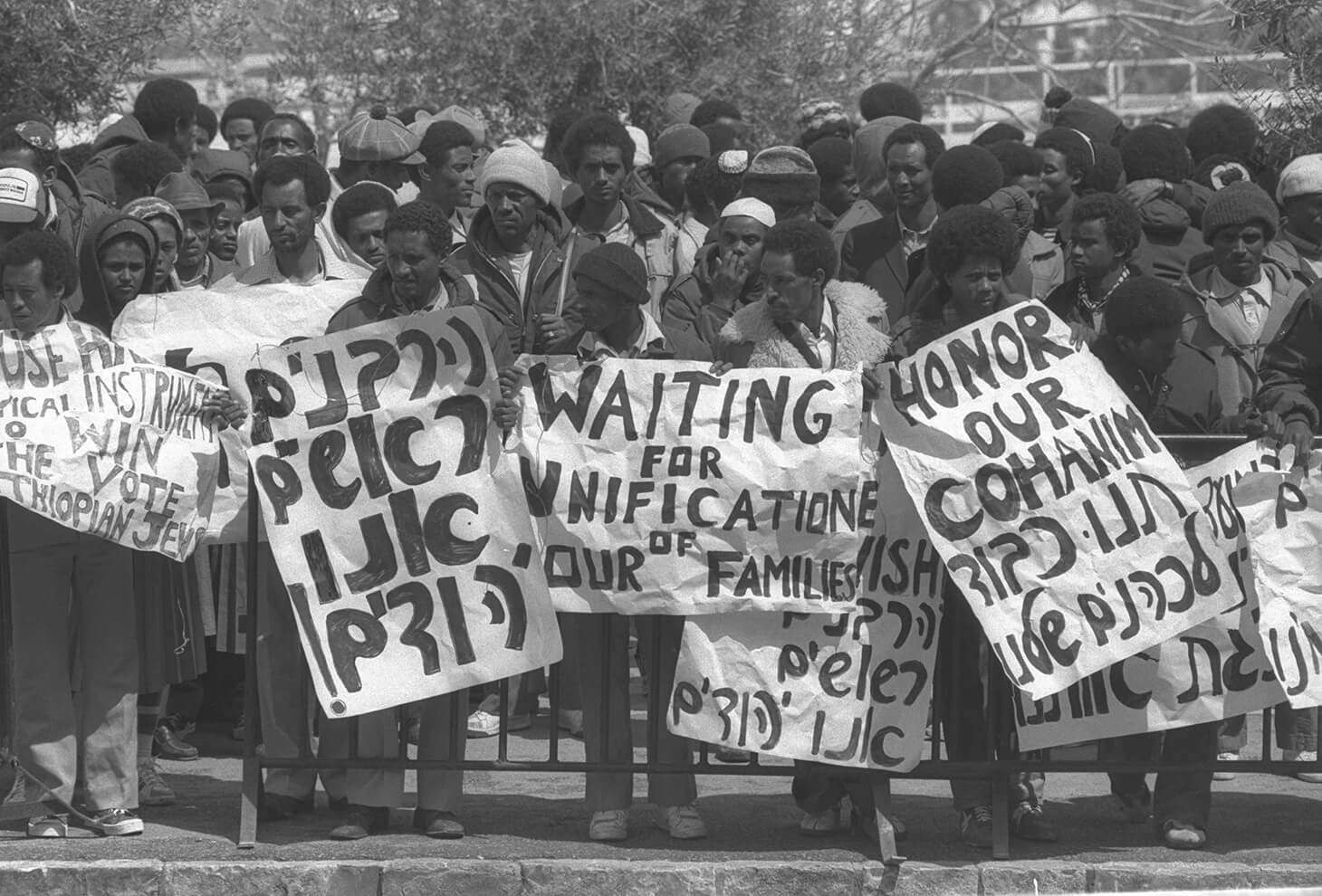

Immigration to Israel continues to this day, and there are still many people waiting for their turn at transit camps.

The immigrants who arrived were initially housed in temporary absorption centers: trailer sites and hospitality centers managed by the Jewish Agency.

The absorption teams at these centers helped the new immigrants adapt and become familiar with the various systems and services related to health, education, employment and more.

After the immigrants moved into permanent homes, the authorities created programs and special mechanisms meant to ease their absorption process. These included absorption hotlines, a special department in the army for the immigrants, and special employment training programs. However, instead of providing the immigrants with practical tools to deal with everyday life in Israel, these programs actually created incubators that separated the immigrants from society and led to an increase in the prevalence of prejudice and racism toward immigrants and their children.

Housing

As aforementioned, Ethiopian immigrants in the eighties and nineties were not directly absorbed like other immigrants, but rather were housed in hospitality and absorption centers for an extended period of time. This policy of indirect absorption was justified by the government due to the low level of education of the immigrants, the minimal resources that they brought with them, and a range of other reasons.

The policy established that the absorption process would be spread across the course of five years: at the first stage, immigrants would be housed in temporary homes at absorption centers, and after one year, they would move to permanent housing.

In the eighties, most of the immigrants were referred to public housing in selected towns, mainly on the geographic and social periphery of the country. In the nineties, after Operation Solomon, the policy was changed and it was decided that in light of the significant gaps that had developed after so many immigrants were referred to the periphery, those who arrived in Israel after 1991 would be entitled to enlarged mortgages and grants in order to purchase apartments in specific areas, mainly in central Israel; affluent areas were not included. The result of this policy was that Ethiopian immigrants who bought apartments were concentrated in disadvantaged neighborhoods in central Israel.

Employment

Those who shaped the absorption policy for the immigrants of Operation Moses reached the conclusion that a special system should be established for them for their professional integration. The reasoning was that their education and professional skills were not compatible with the Israeli economy. This system was formulated as a joint effort of the Ministries of Absorption, Labor, and Education, as well as other bodies such as the JDC and the Jewish Agency.

First, professional training courses for Ethiopian immigrants only were created. The screening process for these courses was primarily based on the immigrants’ gender and years of schooling. Most of the men were trained in professional vocations in the industrial field and in construction, and most of the women were taught nursing professions, sewing, and silversmithing. Those who had completed 12 years of school or more were referred to courses that trained them as dental assistants, educational social workers, bookkeepers, and other occupations.

Second, immigrants were provided with assistance in adapting to the Israeli workforce, in the form of employment preparation workshops and personal guidance from employment coordinators. These coordinators guided the immigrants during the training courses, the hiring process, and even afterward: in navigating their rights with their employers.

Beginning in the mid-nineties, additional programs were opened for Ethiopian immigrants, such as the Women of Valor program for promoting female employment, and projects to promote entrepreneurship and small businesses.

Education

During the wave of immigration in the eighties, the government decided that the children of the community would be enrolled in the religious public educational system. The rationale was that they should be given an opportunity to become familiar with Orthodox Judaism and that a religious education was closer to their values as a traditional society. This decision was contrary to the general policy, which provides parents (including immigrants) with the option of choosing where their children will learn, and it was made without consulting with the Ethiopian community itself.

Another decision that was made was that teenagers would be sent to religious dormitory schools affiliated with Aliyat HaNoar. This policy had a number of consequences. First, the community’s youth were educated in a defined, limited study track, especially since until 1992, they were primarily referred to vocational tracks and not to theoretical tracks. Second, they were distanced from their families and the responsibility for their education shifted from their families to their schools. If this decision was fairly logical in the eighties, since many teenagers arrived in Israel without their parents (although those who immigrated with their parents were also sent to dormitories across the board), it was not appropriate for the immigrants in Operation Solomon, almost all of whom came as complete families. Indeed, beginning in the mid-nineties, the trend of referring Ethiopian teenagers to dormitories decreased.

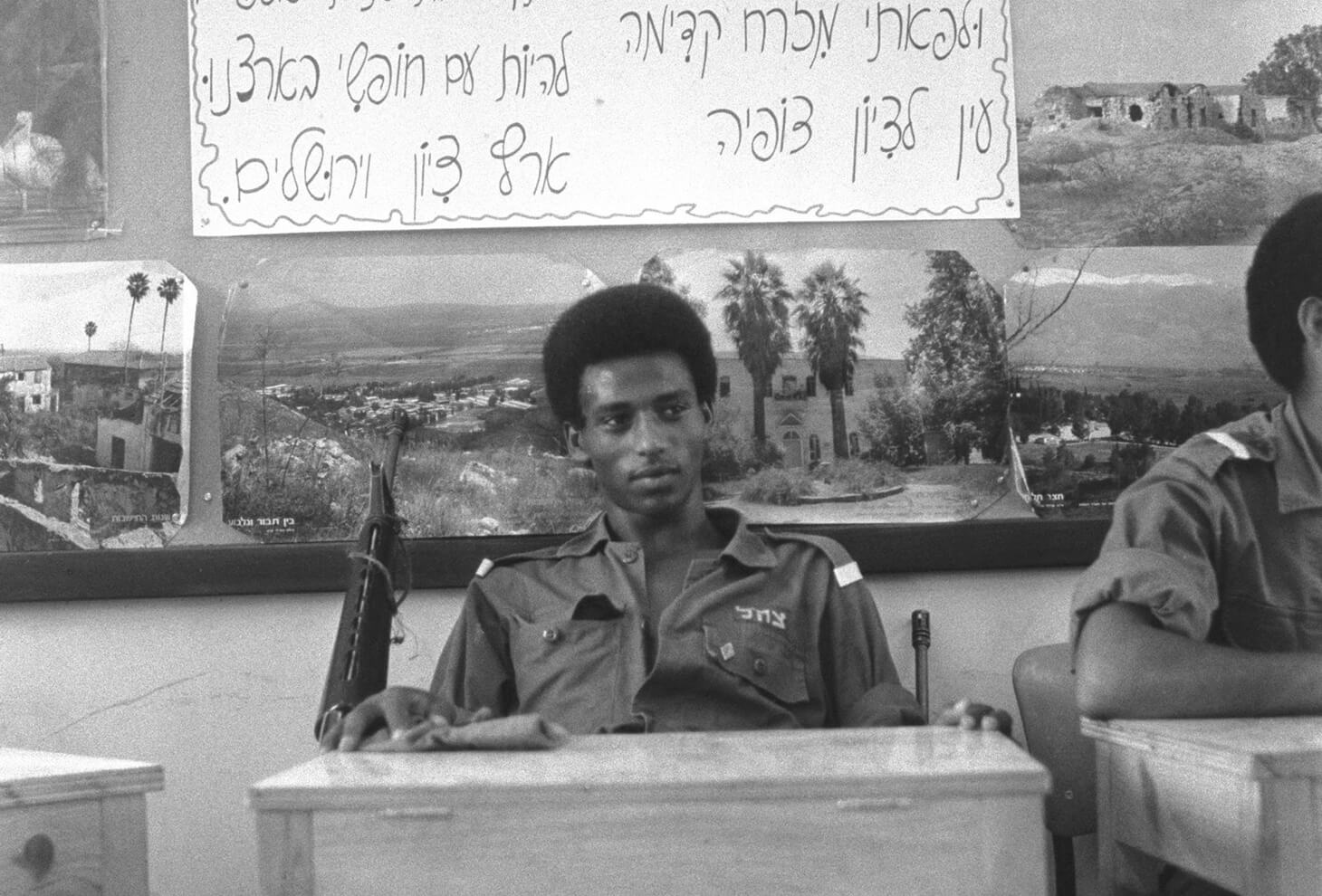

Army

In the early eighties, the IDF, together with the Jewish Agency, Aliyat HaNoar, and the Ministry of Absorption, created a program for absorbing Ethiopian immigrants in the army. This program included preparation for army service, assistance during their service, and preparation for their discharge. At the beginning of their service, before their official training began, the soldiers underwent a special three-month preparatory course called Magen Zion. The course was meant to help Ethiopian immigrants transition into the military framework and its requirements, as well as to provide enrichment in areas such as Hebrew language and Israeli history. At first, all Ethiopian immigrants were referred to the course automatically (although they were given the option of declining). In the early nineties, this policy was changed, and candidates for military service were classified into three groups according to their scores during the screening process. One group was referred to the course in its original format, a second was provided with a shortened, one-month course, and the third group was recruited directly in the regular army training program.

During their service, the soldiers were provided with a special officer who was responsible for Ethiopian immigrants in the IDF and served as an address for their needs in the event that they did not find solutions through the regular system. In addition, the army encouraged soldiers who did not have any professional training to take courses that would provide them with a profession that they could practice during their military service and after their discharge. Prior to their discharge from the army, the soldiers were prepared for civilian life with explanations regarding benefits available for discharged soldiers, career consulting, and more.