Aliyah and Attempts at Aliyah

The longing, yearning, and dreams of Jerusalem never stopped throughout the history of Ethiopian Jewry, and were expressed in the words of their prayers, on the Sigd holiday, in songs, at joyous times and times of mourning. Jerusalem was and remains their deepest desire. In 1862, the spiritual leader Abba Mahari led many members of the community on a journey toward the Red Sea, in order to reach Jerusalem. However, the journey failed; many perished and those who remained were forced to turn around and head back.

Despite the crisis that the community experienced following this failed immigration attempt, their desire to realize this dream did not die. The arrival of Joseph Halevy in Ethiopia that same decade opened up a line of communication with the rest of the Jewish world and with Jerusalem in particular. Halevy’s student and follower, Yaakov Faitlovitch, established Jewish schools in Ethiopia with the assistance of Professor Taamrat Emmanuel, Gete Yirmiahu, and Yona Bogale, and they encouraged worldwide Jewry to recognize the Beta Israel. A small number of the community’s youth were sent to schools in Europe and Israel, which further encouraged the community to realize its dream of immigrating to Jerusalem.

There are letters from the early twentieth century written by leaders of the Beta Israel such as Lika Kahanat Berhan Baruch and Yona Bogale to Jewish leaders in Israel and worldwide, expressing their desire to reach Israel and unite with the rest of the nation. These leaders did not suffice with letter writing; their activities included traveling on lecture tours to raise awareness of the cause.

After the establishment of the State of Israel, the Israeli government decided not to initiate an operation to bring the Jews of Ethiopia to Israel. In addition, they were not included in the Law of Return. This was due to doubts regarding their Jewish status. Despite the state’s reservations, about 200 members of the community immigrated to Israel independently over the years. This small community that lived in Israel worked tirelessly to bring the rest of Beta Israel to Israel, through petitioning, protesting, and holding meetings with government entities in Israel and worldwide. In addition, leaders of the community in Ethiopia, activists, and organizations in North America such as the American Association for Ethiopian Jews (AAEJ), put pressure on the Israeli government and sent representatives on campaigns around the world in order to increase awareness of the issue among foreign governments and Jewish communities in the Diaspora, who then also put pressure on Israel.

At the end of the seventies, all of these efforts finally bore fruit, when the state began to initiate immigration operations, some of which were kept secret. Aside from the two large immigration operations, Operation Moses and Operation Solomon, many other operations were conducted, and essentially, immigration from Ethiopia continues to this day.

Independent and Illegal Immigration

(1935-1979)Even before the large immigration operations, Jews immigrated to Israel from Ethiopia on their own. There are records of the immigration of a few individuals – both young adults who came alone, and families – as early as the 1930s and 1940s.

After the establishment of the State of Israel, independent immigration became more complicated, as the authorities were uncertain regarding recognition of the Jewish status of the Beta Israel. Nevertheless, as of the 1950s, young adults from the community occasionally managed to reach Israel on tourist visas. When these visas expired, they faced expulsion and had to undergo a pro forma conversion process in order to remain in Israel as Jewish immigrants. The other option was to hide from the authorities. The state also made it more difficult to immigrate by establishing stricter procedures at the Israeli consulate in Addis Ababa for granting visas to members of the community.

The formal obstacles preventing independent immigration were removed by the State of Israel in 1975, when the Law of Return was applied to the Jews of Ethiopia. But by that time, obstacles had already been imposed on the Ethiopian side, as the diplomatic ties with Israel were severed and due to the new government that rose to power, which made it very difficult for Ethiopian citizens, including Jews, to leave the country.

About 200 immigrants reached Israel by means of independent and illegal immigration.

The Immigration of the Beta Israel via Sudan (Operation Brothers)

(1979-1990)Between 1979-1990, thousands of Ethiopian Jews immigrated to Israel via Sudan. This activity began after activists such as Ferede Aklum, Baruch Tegegne, Zimna Birhane and Zecarias Yona met with agents of the Israeli Mossad. Thus, an infrastructure for a new route of immigration was laid for the Beta Israel. Members of the community set out on the difficult journey to Sudan on foot. From there, they were secretly brought to Israel.

The journey to Sudan and the time spent in refugee camps there were fraught with difficulties and suffering, and resulted in a large number of deaths. The first challenge that the travelers faced was to hide their departure from their villages, for fear of being arrested by the authorities. Preparations for the journey were made secretly, and sometimes family members left on separate trips, at different times, in order not to arouse suspicions. People of all ages embarked on these journeys – men, women, the elderly, and children. Pregnant women also participated in these journeys, and some gave birth on the way.

The journey took between a few weeks to a few months, and was usually made on foot. They would walk at night and rest during the day, for fear that they would be discovered and caught by the authorities, and for fear of robbers. The extreme heat during the summer months was also a factor in this decision, but in the unsettled regions, they would walk in the day as well. Throughout the entire journey, the travelers had to hide from government soldiers and from robbers and rapists who ambushed convoys. They walked through difficult terrain – forests, rivers, mountains, and deserts, and had to watch out for wild animals and snakes. Another challenge was the limited amount of water and food that they could carry with them, a problem that worsened toward the end of the journey, which passed through the desert. The exhaustion, hunger, thirst, and heat overcame many of the travelers. Families had no choice but to bury their loved ones, who perished before realizing their dream, hastily on the sides of the road. Afterward, they had to find the strength to keep going.

When they reached Sudan, the travelers were placed in refugee camps under the supervision of the Red Cross. The living conditions in these camps were very severe. The lack of edible food and water, the crowdedness, the extreme heat, and the poor sanitary conditions resulted in diseases that took many lives, especially of babies and children. Acts of robbery and rape were common in the camps, and members of the community faced another danger as well: harassment by the non-Jewish refugees and the Sudanese because of their Judaism. They tried to hide their identities and keep the commandments secretly. The incredible strength of character that kept the travelers going throughout their difficulty journeys was even more critical to them in the camps, since they had no way of knowing how long they would stay there in these difficult conditions and when they would finally be able to immigrate to Israel. They remained in the camps for months or even years.

While they waited, the Jews in the camps received assistance from a committee of activists composed of members of the community who were in contact with the Mossad. They were referred to as the “Commité.” Members of the Commité were involved in various tasks: identifying Jews (who, as aforementioned, were hiding their identities) among the refugees, distributing aid money and medications, obtaining exit visas to leave the camps, placing Jews in hideaway apartments to await their immigration, and finally – smuggling them to the meeting point with the Mossad, from which they immigrated to Israel. They did this for years, constantly risking their lives. Some of them were even arrested by the Sudanese and were viciously tortured for their Zionist activities.

In recent years, there have been those who reminded that among the Commité members, there were activists who misused the trust placed in them and their power, severely abusing women from the community. At the same time, it is important to remember that this was the minority. Most of the activists acted courageously and with dedication on behalf of the community, even though this meant deferring their own immigration. Some of them even returned to Ethiopia and Sudan after they immigrated in order to help with additional operations.

Immigration via Sudan took place in a manner of ways that were planned by the Mossad. According to the first method, exit visas were obtained from Sudan in an ostensibly legal way, by presenting forged papers showing that various countries had agreed to take in the visa applicants as refugees. After the visas were obtained, the immigrants were flown on regular commercial flights to stopover countries, from which they were flown to Israel. The second method involved smuggling the immigrants from the refugee camps to Port Sudan. From there, they sailed to Israel with the Israeli Navy. The cover that allowed members of the Mossad to remain in the region for an extended period of time was a resort village that they operated parallel to their secret operations. The third method involved smuggling the immigrants to isolated locations in the Sudanese desert where there were abandoned aircraft landing pads (or sometimes, makeshift ones). From these hidden landing pads, the Israeli Air Force flew the immigrants to Israel.

In the immigration operations via Sudan (including Operation Moses), approximately 16,000 Olim were brought to Israel.

Operation Moses and Operation Sheba

(21.11.1984-05.01.1985)Operation Moses was part of the immigration operations via Sudan. For more information about this wave of immigration and the difficult journey that the community made from Ethiopia to Sudan, see: [LINK]

In 1984, the number of Jews who had arrived in Sudan increased significantly, and at the same time, the sanitary conditions in the camps were constantly worsening. The severe mortality rates led the Israeli government to decide that the operations to save the community to date were not sufficient, and that it was necessary to initiate a larger-scale operation. Diplomatic connections brokered by America led to a secret deal with the president of Sudan, who agreed – in exchange for a sizable sum of money – to allow Israel to fly the Jews out of the country, on condition that the planes would not fly directly to Israel, so that the collaboration with Israel would not be exposed.

The operation was launched on November 21, 1984 using aircraft from TEA (Trans European Airways), owned by a Belgian Jew named George Gutelman. The operation lasted several weeks and thousands of Jews were brought to Israel, but it ended on January 5, 1985 after government entities in Israel leaked information to the media. The publicity was a severe embarrassment to the Sudanese government, who ordered to stop the operation immediately.

In Operation Moses, 6,364 Ethiopian Jews immigrated to Israel. Since the operation was halted before all of the Jews in the camps could be brought to Israel, the American government reached an agreement with the president of Sudan by which the remaining people would be rescued from Sudan in American aircraft. This operation, named Operation Sheba, took place on March 22, 1985. The US Army flew 494 immigrants out of Sudan, while another 100 who received exit visas left on civilian flights.

In Operations Moses and Sheba, approximately 7,000 immigrants were brought to Israel.

Operation Solomon

(23.05.1991-25.05.1991)At the end of 1989, the diplomatic ties between Israel and Ethiopia were renewed after a 16-year freeze, allowing members of the community to immigrate directly from Ethiopia. At the same time, immigration via Sudan had become even more complicated and dangerous, due to changes in the Sudanese government. The Jews of Ethiopia put great hope in this new immigration option, and encouraged by activists from the community and Jewish organizations, most prominently the AAEJ, they left their villages and started to gather around the Israeli embassy in Addis Ababa. While waiting to immigrate, the Jews were assisted at a special complex that included a health clinic, a school, and more. The complex was operated by the AAEJ, Israeli representatives, and Jewish organizations such as the JDC, the Jewish Agency, Almaya, and NACOEJ.

Immigration was a slow process at first; during 1990 and at the beginning of 1991, only about 7,000 of the 20,000 people awaiting immigration reached Israel. Throughout the entire period, activists from the Ethiopian community put pressure on the Israeli government to expedite the process and unify families who had been separated after the immigration efforts via Sudan had ceased. This pressure increased as the security situation in Ethiopia gradually began to deteriorate, due to the raging civil war. Eventually, in April 1991, the decision was made to bring all of the residents of the complex to Israel urgently, as the rebels were approaching Addis Ababa. However, Ethiopian President Mengistu Haile Mariam delayed the exit visas for the Jews in order to pressure Israel and the US into providing him with monetary aid for his war against the rebels. The Ethiopian government finally agreed to allow the immigration operation in exchange for 35 million dollars, donated by American Jews. At that time, the rebel forces were already prepared to conquer Addis Ababa, but thanks to American brokerage, their invasion of the city was postponed for a few days, until the operation was completed.

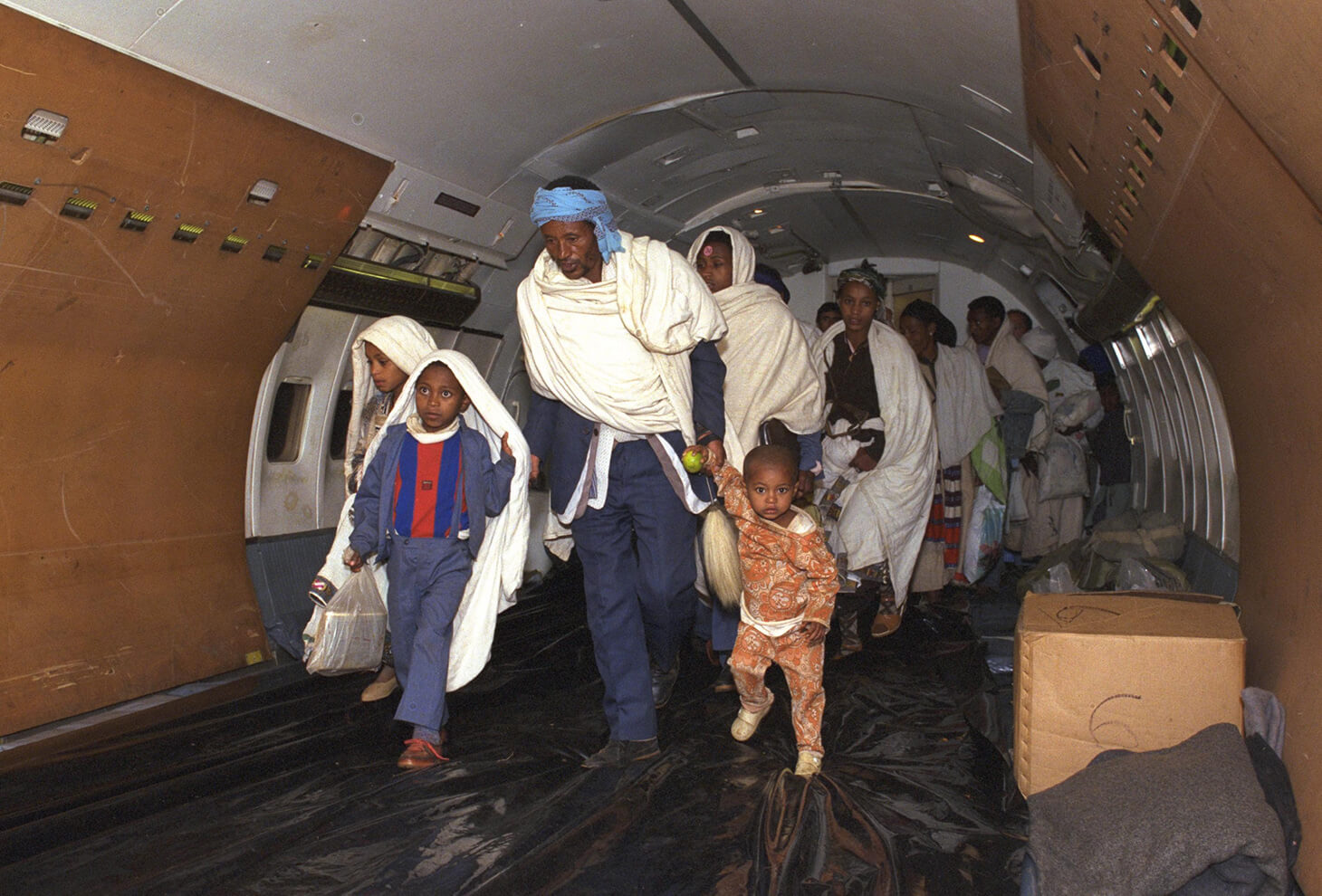

The complex operation, known as Operation Solomon, was a joint effort of the IDF, Mossad, Foreign Ministry, Jewish Agency, and long-time Ethiopian immigrants in Israel who helped the new immigrants during the flights. The operation was launched on the night of May 23, 1991; approximately 120 people onsite (themselves waiting to immigrate as well) were responsible for concentrating the thousands of Jews at the Israeli embassy. From there, they were driven in buses to the airport. The next morning, nonstop flights of 34 aircraft began to fly the immigrants to Israel. In order to put as many immigrants as possible onto each plane, all of the seats were removed. One of the flights even set a Guinness world record for the most passengers in one aircraft (1,088 passengers, two of whom were born mid-flight). The operation ended on the morning of May 25.

Operation Solomon was the largest immigration operation to bring Jews to Israel in history. Over the course of 36 hours, 34 aircraft flew over 14,000 immigrants to Israel.

Immigration of the Jews of Qwara

(1992-1999)Until the nineties, there were hardly any Jews who immigrated to Israel from the province of Qwara. The reason was that rebels controlled this area, making it very difficult to leave. When the civil war in Ethiopia ended in the summer of 1991, the region became accessible and representatives from the Jewish Agency and the JDC were sent to find people eligible for immigration to Israel. The process of finding eligible candidates and bringing them to Israel was slow and continued throughout the nineties. After public pressure was applied by relatives of the Jews of Qwara and by activists supporting Ethiopian Jewry, the Israeli government decided in 1998 to expedite the process for this community. A year later, almost all of the remaining Jews were brought to Israel.

The immigration efforts for the Jews of Qwara resulted in the arrival of approximately 5,000 new immigrants in Israel.

Immigration of the Zera Beta Israel community

(1992-2022)The roots of this community were Ethiopian Jews who converted to Christianity from the 19th century and onward, but did not assimilate with the general Christian population, instead remaining at somewhat of an interim status between the two communities. Sometimes, they even maintained their social connections with their Jewish relatives and the Jewish community in general.

Among the thousands who gathered in Addis Ababa before Operation Solomon, there were also about 2,000 members of the Zera Beta Israel community. However, the Israeli government decided not to include them in the operation because they were not eligible under the Law of Return. This community remained at the waiting complex in Addis Ababa and continued to fight for their right to immigrate to Israel, with the help of various organizations, primarily the North American Conference on Ethiopian Jewry (NACOEJ). Over time, more and more members of the community arrived at the complex.

In 1992, a ministerial committee headed by the absorption minister at that time, Yair Tzaban, recommended bringing over those members of Zera Beta Israel who had first-degree relatives in Israel, on the grounds of family reunification. After a few years, due to public pressure, it was decided to forfeit this condition and allow all of those at the complex (approximately 4,000 people) to come to Israel and undergo a process of “returning to Judaism” in Israel. Over the years, a few more operations were conducted to bring members of this community to Israel. However, even today, after the last operation (“Tzur Yisrael” in March 2021), thousands more, who have relatives already in Israel, are still waiting at the complex in Addis Ababa and in an additional complex that was established in Gondar.

The immigration efforts for the Zera Beta Israel community resulted in the arrival of approximately 50,000 immigrants in Israel to date.